Illustrated Masterpiece Architecture Tour with Hiroshi Miyazawa & the Heritage Business Lab

Episode 4

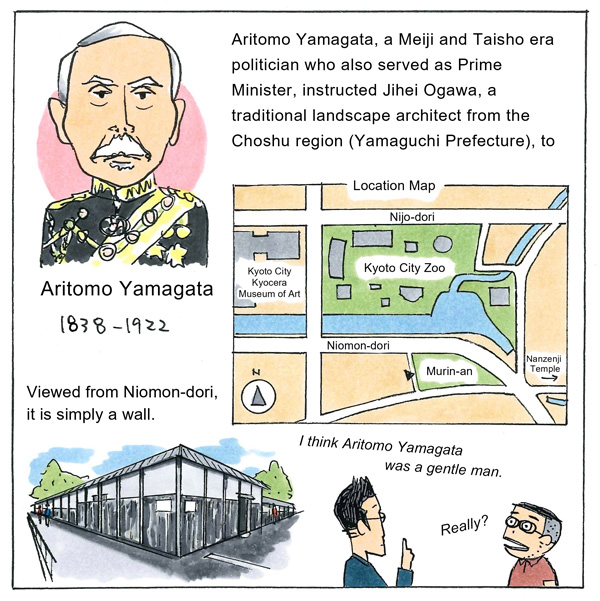

"Calculated looseness; was Aritomo Yamagata a great architect?"

Scroll Down

Our current destination:

Murin-an

Looking at Murin-an Garden, one can see that Aritomo Yamagata was a gentle person. “What?”you may ask. “The same scary-faced Aritomo Yamagata depicted in Japanese history books?” And why does a tour of famous architecture take us to a garden, of all places? Once again, Takao Nishizawa of the Nikken Sekkei Heritage Business Lab guides us on a different course than the average architecture buff. That is why I enjoy this series.

The entire facility consists of a garden and three buildings: the main building, a Western-style house, and a teahouse. The garden was created by Jihei Ogawa VII (1860-1933), and is considered a modern Japanese garden masterpiece. A legendary landscape architect regarded as a pioneer of modern Japanese gardens, Jihei Ogawa received detailed instructions from Yamagata for Murin-an. It is said that Yamagata allowed Ogawa's talent to blossom.

What does "Murin-an" mean?

The second-generation Murin-an was a villa in Kiyamachi Nijo, Kyoto (now called Ganko Takasegawa Nijoen). The third-generation facility is here in front of Nanzenji approach in Kyoto. It is said that Yamagata's decision to build the third Murin-an in this particular location was due to movements in the political and business worlds to develop the area around Nanzenji Shimogawara as a villa area. He seems like a scary politician, Mr. Nishizawa. “Anyway, please take a look.” He seemed confident that I would definitely like it. Let's go in.

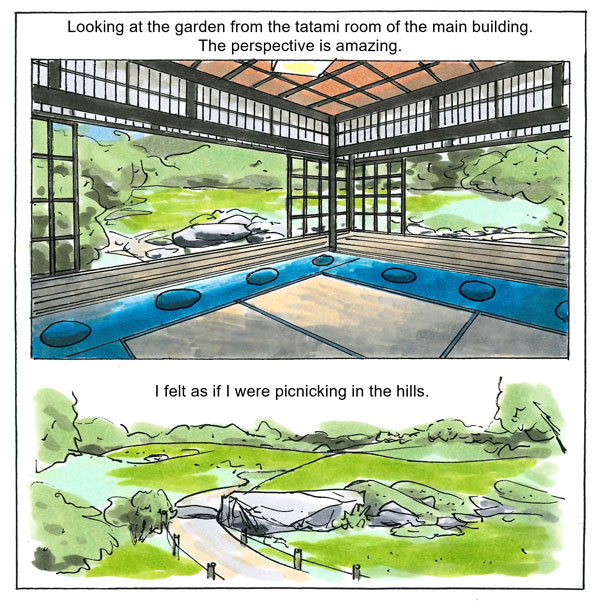

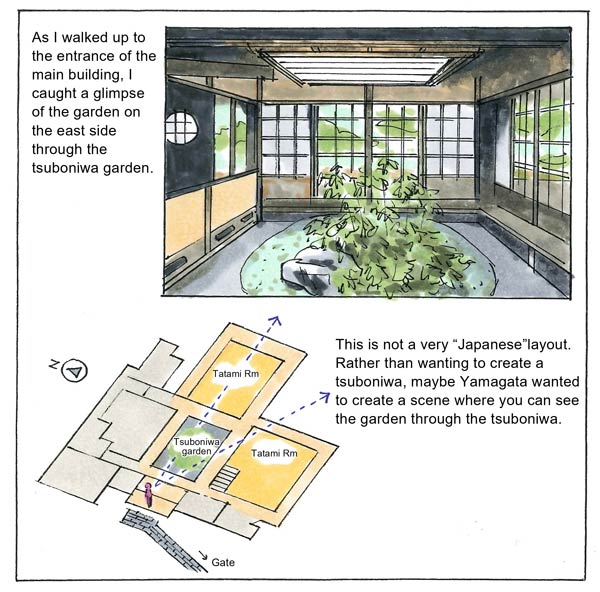

As soon as we entered the west entrance, we found the two-story wooden main building (both the architect and the builder remain unknown). We went up to the entrance of the main building, walked around the tsuboniwa garden and entered the tatami room on the east side, at which point I couldn't help but exclaim, “Oh!”

Extensive use of the lawn area creates a splendid line-of-sight break

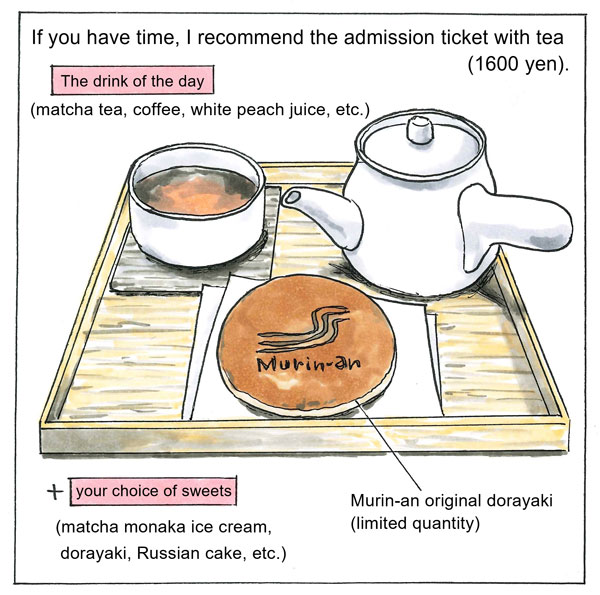

The facility is owned by the city of Kyoto, but since 2016 it has been managed and operated by Ueyakato Landscape, under a “designated manager” system. The entrance fee is 600 yen. If you have come all this way, I recommend having tea in the tatami room. An admission ticket with a cup of tea and sweets is 1,600 yen.

Photo 1: Second floor of the main building

Photo 1: Second floor of the main building

A garden viewed from a building?

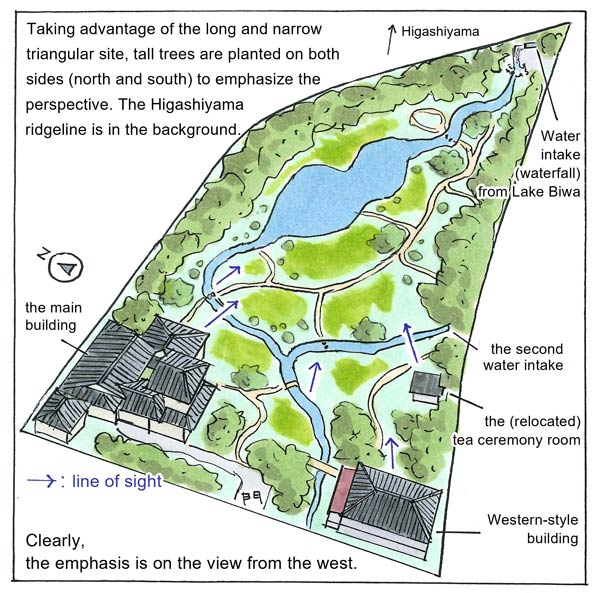

One of the reasons why I think so is due to the layout of the garden. From the main building, the front (west) side is open to the lawn. As you move to the back (east), tall trees come up from both sides (north and south). This is probably to emphasize the sense of perspective at the spatially limited site. And above the east side greenery, the Higashiyama ridgeline offers a response to the perspective of the garden.

Photo 2: Appearance of the main building

Photo 2: Appearance of the main building

Skillful use of perspective and scenic undulations

The "manners" pertinent to Japanese gardens, such as stepping stones, gravel paths, and boundaries, are too profound for me to explain as an outsider. Please ask the staff who guide you there. However, even if you aren’t aware of such manners, there are many things to discover for architecture lovers.

For example, the way the water flows. Water intake from Lake Biwa Canal is at the east end of the site; water from there enters like a waterfall all at once, then spreads out like a pond on a gentle slope, becoming a narrow stream near the main building. The pond is not visible from the tatami room of the main building, which may induce you to want to take a walk in the garden.

Photo 3: Waterfall

Photo 3: Waterfall

Photo 4: Pond

Photo 4: Pond

Photo 5: The stream

Photo 5: The stream

Involving citizens to "nurture" cultural assets

The Good Design Award and the Japan Institute of Landscape Architects Award were both given to Murin-an managers for involving the public. One merit recognizes the "Murin-an Fostering Fellows," a system where citizen volunteers are trained in the value of the garden as a cultural asset and are encouraged to work at their own pace in the facility, nurturing it together.

The garden’s other merit is the variety of events that it hosts. In addition to tea and Japanese sweets events, unexpected projects such as photo and art exhibitions are also held there.

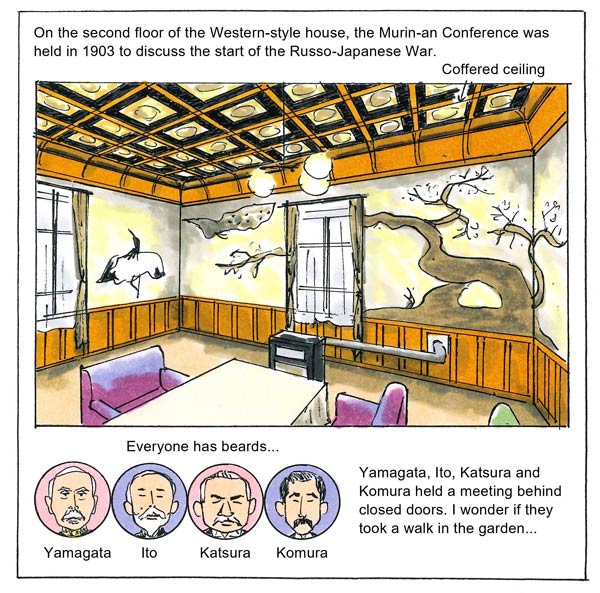

The Western-style house hosted the Murin-an Conference, a Meiji era turning point

Architectural Summary

Site area: 3,135 m2 (area designated as cultural property)

Client: Aritomo Yamagata

Landscape architect: Jihei Ogawa VII

Garden construction period: 1894-1896

Main Building

Completion: 1896

Architect: Unknown

Builder: Unknown

Structure / number of floors: wooden, one story, partial two-story

Western-style house

Year of completion: 1898

Architect: Takamasa Niinomi

Builder: Mannosuke Shimizu

Structure and number of floors: brick, two stories

Tea House

Completion: relocated around 1895

Structure / number of floors: wooden, one story

Visitor’s Guide

Access: Kyoto City Bus, Kyoto Okazaki Loop, four-minute walk from “Nanzenji/Sosui Kinenkan/Dobutsuen Higashimon-mae”stop, or a 10-minute walk from Jingumichi or “Okazaki Koen/Bijutsukan/Heian Jingu-mae” stop. About a seven-minute walk from Kegami Station on the Kyoto Municipal Subway Tozai Line. About a 20-minute taxi ride from Kyoto Station.

Open hours: 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. April to September, 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. October to March (last admission 30 minutes before closing time)

Admission: 600 yen (free for children under elementary school age, free for elementary school students living in the city and persons over 70 years old)

Murin-an Cafe: 9:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Official website: https://murin-an.jp/en/

Interview, illustrations and text by Hiroshi Miyazawa

Writer, illustrator, editor, Editor-in-chief of BUNGA NET

(*: co-authored with Tatsuo Iso)

Takao Nishizawa

Associate, Heritage Business Lab, Facility Solution Group, New Business Development Dept./ Ph.D. (engineering)

His project credits include the seismic retrofitting of the Aichi Prefectural Government Headquarters and Aichi Prefectural Police Headquarters. He supervises the design of complex buildings where new construction and seismic retrofits are integrated. These include Kyoto City Hall, currently under construction. Mr. Nishizawa leverages his experience in seismic retrofitting of buildings with high historical value. He has led the Heritage Business team since 2016 while continuing his work on structural design.