Illustrated Masterpiece Architecture Tour with Hiroshi Miyazawa & the Heritage Business Lab

Episode 5

Two "Napolitans" at an Ueno Hideaway

Scroll Down

Our current destination:

The International Library of Children's Literature, National Diet Library

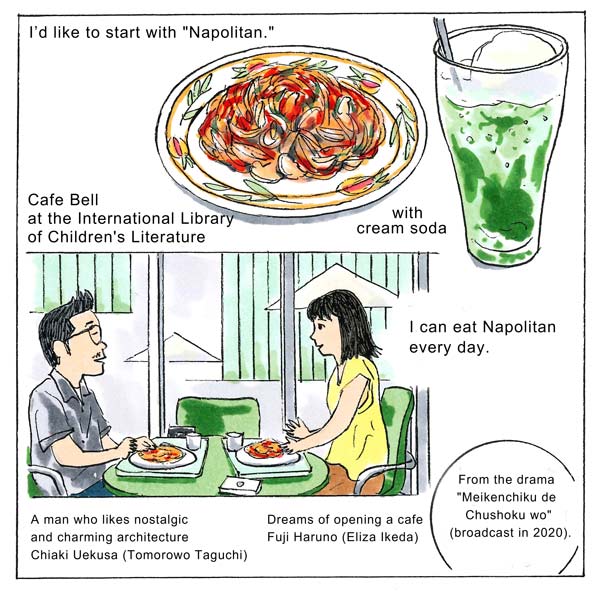

In this episode, I will start with the story of "Spaghetti Napolitan.” I visited the International Library of Children's Literature, National Diet Library" in Ueno, Tokyo. It is said that an increasing number of people have been ordering Napolitan at the first floor "Cafe Bell" restaurant since about a year ago.

In fact, when I searched for Cafe Bell on a restaurant review site, I found the following post. “I had lunch there after an architecture tour. I was looking for the Napolitan dish that was served in a popular Japanese TV drama.

“The Napolitan was full of ingredients and very filling. It had a simple ketchup flavor, but was delicious. I can’t imagine anybody who wouldn't like it. It's been a while since I've had Napolitan, but this old-school Napolitan was perfect for eating while looking at the retrofit architecture.”

Meikenchiku de Chushoku wo: the setting for the drama

Meikenchiku de Chushoku wo is a TV drama that aired 10 times from August to October 2020 on BS TV Tokyo and TV Osaka in the midnight slot. Each time, Chiaki Uekusa (Tomorowo Taguchi), who enjoys touring architecture, and Fuji Haruno (Eliza Ikeda), who dreams of someday opening a café, visit one architectural site, and the story slowly progresses in parallel. This facility was the setting for the ninth episode. The scene where Fuji, after one facility tour, dines on spaghetti Napolitan while saying, "I could eat Napolitan every day," left an impression.

Photo 1: Café interior

Photo 1: Café interior

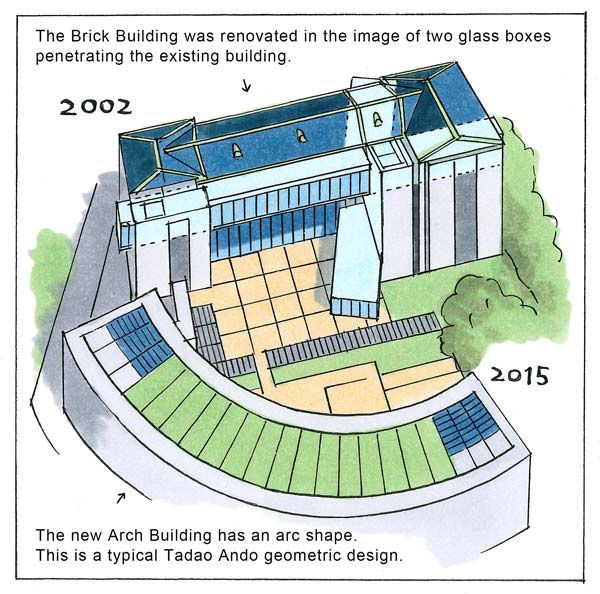

Bold renovation and Tadao Ando’s participation

...... and so far, this is almost a copy of the facility's official website. Those who have seen the drama may be thinking, "I already knew that.”

So, here is the first piece of special information. The 2002 renovation was not solely Tadao Ando’s design, but a collaborative effort with Nikken Sekkei, Mr. Nishizawa’s company (although he was not directly involved in the project). The concept of two glass boxes penetrating the existing building belongs to Ando. However, Nikken Sekkei worked on enhancing building safety with seismic isolation technology and on reproducing the detailed interior and facades.

Photo 2: Seismic isolation level

Photo 2: Seismic isolation level

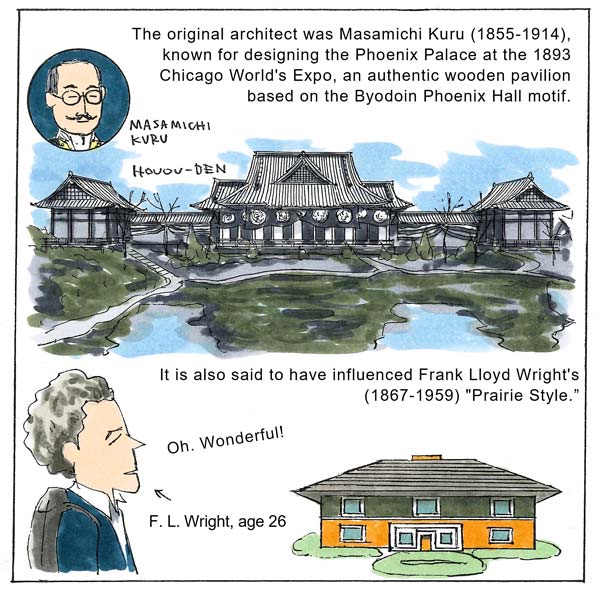

The existing building’s architect also designed the Phoenix Palace!

As an engineer at the Ministry of Education, Kuru designed many educational facilities. Sogakudo of the Former Tokyo Music School (completed in 1890, designated as an Important Cultural Property), also designed by Kuru, is located near this facility. He was also responsible for "Ho-o-den (Phoenix Palace)," the Japanese pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World's Expo, which became globally influential.

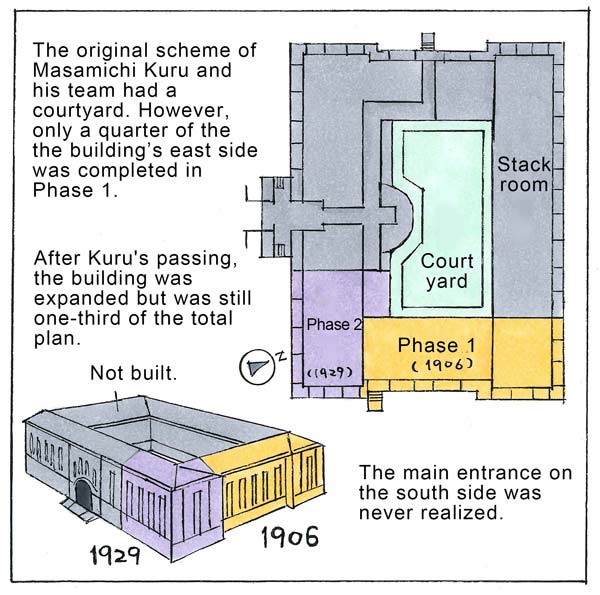

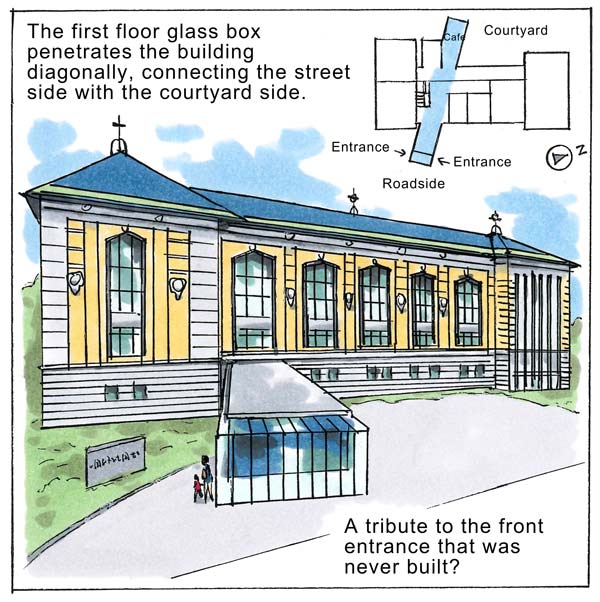

Unfinished main entrance with glass box

Although the library did not collapse in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, it was severely damaged. In 1929, a reinforced concrete extension was built on the north side as part of the second phase of construction. This is what remains today.

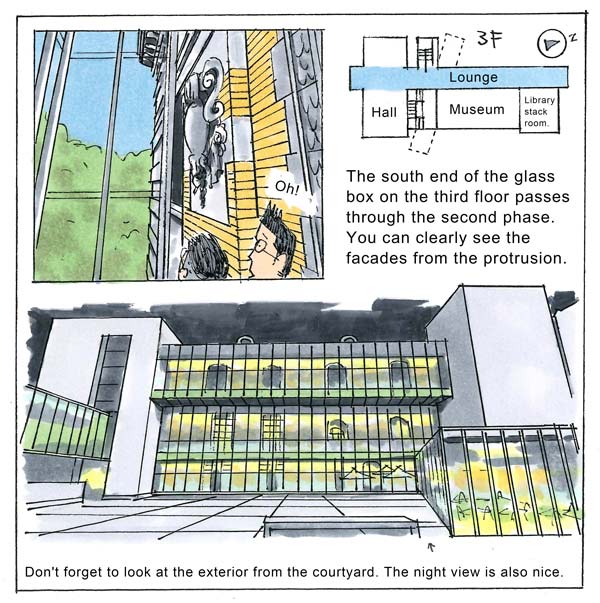

As you can see from the original plan, the "main entrance" that Kuru and others had in mind was not built. Ando's idea for the Heisei-era renovation was to have two glass boxes penetrate the existing building, with one running diagonally from the street side of the first floor to the courtyard side. The other is a glass box that “floats in mid-air” on the third floor on the courtyard side, penetrating the 1929 extension.

Photo 3: Looking down on the Arch Building and courtyard from the Brick Building

Photo 3: Looking down on the Arch Building and courtyard from the Brick Building

Viewing the not normally visible exterior walls and facades

Photo 4: Ceiling of the Gallery of Children's Literature

Photo 4: Ceiling of the Gallery of Children's Literature

Napolitan, a bold Japanese idea

Photo 5: Spaghetti Napolitan & soda

Photo 5: Spaghetti Napolitan & soda

The first brick library (the Imperial Library) designed by Masamichi Kuru was a full-fledged western-style building in the Renaissance style, and as such, "authentic pasta,”in a manner of speaking. In the Showa era (1926-1989), the library was extended and rearranged, and in the Heisei era (1989-2019), it was boldly rearranged to become a "Napolitan" building. If you eat Spaghetti Napolitan at the cafe in the ILCL courtyard while thinking about this......it may taste even more delicious.

Architectural Summary

Location: 12-49 Uenokoen, Taito-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Brick Building

Original design: Masamichi Kuru, Hideo Mamizu, et al

Renovation of the entire Brick Building: 2002

Renovation design: Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Nikken Sekkei Ltd

Renovation work: KONOIKE CONSTRUCTION CO., LTD.

Structure: Steel-reinforced brick for the Showa era portion; Reinforced concrete for extensions

Number of floors: one basement floor, three floors above ground

Total floor area: 6,671.63 square meters

Storage capacity: Approx. 400,000 volumes

Arch Building

Design: Tadao Ando Architect & Associates, Nikken Sekkei Ltd

Construction: The Zenitaka Corporation

Structure: Steel-framed reinforced concrete (partially steel and reinforced concrete)

Scale: Two floors below ground, three floors above ground

Total floor space: 6,184.11 square meters

Storage capacity: Approx. 650,000 volumes

Visitor’s Guide

Library hours: 9:30 - 17:00

Cafeteria hours: 9:30 - 16:00

Access: 10 min. walk from JR Ueno Station, Park Exit

Official website: https://www.kodomo.go.jp/english/

Interview, illustrations and text by Hiroshi Miyazawa

Writer, illustrator, editor, Editor-in-chief of BUNGA NET

(*: co-authored with Tatsuo Iso)

Takao Nishizawa

Associate, Heritage Business Lab, Facility Solution Group, New Business Development Dept./ Ph.D. (engineering)

His project credits include the seismic retrofitting of the Aichi Prefectural Government Headquarters and Aichi Prefectural Police Headquarters. He supervises the design of complex buildings where new construction and seismic retrofits are integrated. These include Kyoto City Hall, currently under construction. Mr. Nishizawa leverages his experience in seismic retrofitting of buildings with high historical value. He has led the Heritage Business team since 2016 while continuing his work on structural design.