“Human Motion” and “Diversity on the Streets” Connected with the Urban Core (Part I)

Scroll Down

Today, the streets of Shibuya have become the stage for large-scale redevelopment. Here to talk about Shibuya’s redevelopment projects are Kazuko Akamatsu (right), design architect at Coelacanth and Associates for the opening of Shibuya Stream (also simply known as “Stream”) in 2018, and Shigeru Yoshino (left), designer for “Shibuya Hikarie” (also known as “Hikarie”), constructed in 2012, ushering in the dawn of redevelopment. The keyword here is “urban core”, a base for vertical movement connecting the underground with that above, installed in each block in a single line of flow. What is the shape of the future of Shibuya as seen from these two facilities and two urban cores? Facilitator Kiyoyoshi Okumori, representing Nikken Sekkei’s Urban Development Planning Group, has extensive experience in a number of urban development projects both in Japan and overseas and has been involved in the redevelopment movement in Shibuya since the formulation of the Shibuya Station Precinct City Development Guideline.

TAG

Urban core’s “round” design as the symbol of Shibuya

Yoshino: 12 years ago…that’s a story old enough to have graduated from elementary school twice! (laughs) The escalator hall at Hikarie, which connects the three basement floors to the fourth floor above ground was the very first urban core, but right from the beginning, it also showcased wide-ranging implications as an environmental system. For example, we considered it from the perspective of taking in sunlight as the elevator traveled underground, ventilation through a cylindrical space and releasing heat from the basement.

Akamatsu: Since the urban core of Steam is deep underground, we had talked about wanting to capture natural light in any way we could from the very start. It looks like Hikarie has the same discussions.

Yoshino: Yes. We then decided to make its shape more unique and thought through different plans. Actually, Hikarie’s urban core was initially square-shaped. However, in the discussions about what forms the identity of the urban core should take, Professor Naito said that it should give off the sensation of a “foreign body”. Hikarie itself has a number of square elements, so we looked at a fan-like shape, glass polyhedron and a curtain-drape design.

Akamatsu: How did you arrive at the round shape that is currently used?

Yoshino: Professor Kishii talked about how SHIBUYA109 is also a symbolic form that emphasizes a circular shape, and we finally arrived at the conclusion that a round design was kind of like Shibuya itself. We also thought that the interior space could be moved by shifting and arranging the ring-shaped signage a little at a time.

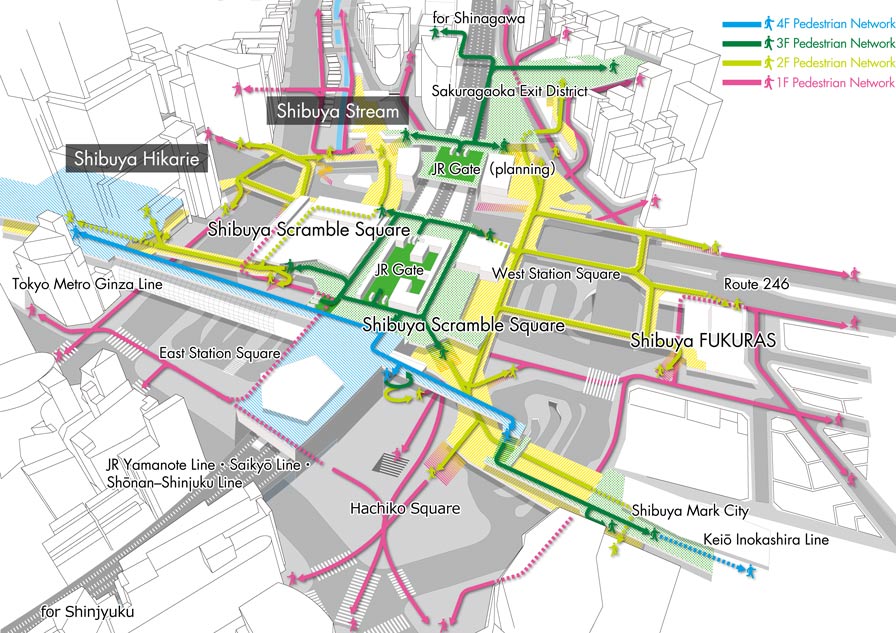

Figure of networks around Shibuya Station (Photo courtesy of Tokyu Corporation)

Figure of networks around Shibuya Station (Photo courtesy of Tokyu Corporation)

Akamatsu: The vital importance of the position of urban cores was imprinted on our brains during the Shibuya Central District Design Conference (laughs). Shibuya really has a valley-like topography, and the area south of Rt. 246 where Stream is located gives the impression that it is somewhat separate from Shibuya. So, the importance of visually communicating the functions of connecting human traffic from the urban core in an easy-to-understand way formed the basis of our discussions. As seen from Meiji-dori, Stream is located in a site that extends far back beyond the Shibuya River, so although the urban core along the street should not present an obstacle, it was necessary for the urban core itself to assert its presence.

Okumori: The design meeting for the core area around Shibuya Station was set up in 2011. It was launched as a space to study and coordinate actions with the aim of guiding the urban landscape in a process that was unique to Shibuya, in order to take advantage of the strengths of the ever-changing and shifting Shibuya. What kinds of discussions took place on the urban core at the design meetings?

Akamatsu: At the design meetings, discussions focused on how appropriate it would be if the buildings, squares and rivers could be developed into one landscape with the urban core in full view. An idea that came up at that time was to have glass screens reflecting the cityscape, with a presence that would have the power to encourage movement to the deeper parts of the structure. While the discussions were going on, the idea that the “urban core is round” came up.

Yoshino: So, the concept came up mid-discussion?

Akamatsu: Yes. It means that each urban core has something in common. The discussions turned to how interesting it would be if the image of a city could be superimposed on the urban core with reflections of the moving landscape of the expressway and Meiji-dori on the glass surface without changing the direction that the glass was used.

Okumori: It is telling that, when actually viewed, two poles have been established: one with a sense of presence and one without. Generally, I think it would be more tempting to include more design factors and functions if it is a place where people gather, but the idea of a simple “glass box” from the very beginning is intriguing.

Akamatsu: Yes. Since the urban core had no other functions other than acting as a flow line, discussions revolved around the idea of something simple from the very beginning. This is an early sketch left by Kojima (Kazuhiro, co-founder of Coelacanth and Associates), who wrote, “The urban core is light.” We thought about how to apply light as we went deeper into the earth, and there were not many options originally other than glass.

"Movement" itself as a new experience

Yoshino: When I went to Hikarie in the summer and I took my hand away from the escalator, I could really feel the heat coming up from the underground levels. Of course, this is a natural way for me to think because this was how the building was designed, but I was relieved to see that it was having the proper effect. However, people who use these spaces and escalators are moving around very quickly. From a designer’s point of view, I would love people to go up and down in a more relaxed manner…Ms. Akamatsu, would you like to add to this?

Akamatsu: Stream’s urban core is not a perfect circle, but a cylindrical polyhedron. When people come up on an escalator and look at the urban core from the Stream side, they can see different lights reflected in the glass, especially at night, and can always see the highway and pedestrian crossings beyond that. It gives off an even more strange feeling than I originally thought, this overlapping of the actual landscape and the images reflected in the glass.

Yoshino: And now it’s an “Instagrammable” landmark (laughs).

Akamatsu: Everyone uploads such beautiful pictures on SNS. There are also photos that look like science fiction films and I think, “Wow! I want this one!” (laughs)

Yoshino: With Stream, the line of flow itself is impressive in its yellow highlights. What kinds of discussions did you have about color?

Urban core of Shibuya Stream

Urban core of Shibuya Stream

Yoshino: So, that was how it came about? At Nikken Sekkei, we created a bright red escalator at Queen’s Square Yokohama, but the yellow color of Stream is very easy to find and draws together the image of the entire city block.

Akamatsu: We had a number of discussions with lighting designer, Izumi Okayasu, who joined the project team, to ensure that the yellow color could be seen properly. We ended up using the same color for signs and marks, and now have a name for the color, “Stream Yellow” (laughs).

Okumori: You both worked on redevelopment at different times. What impressions do you have of each other’s design?

Akamatsu: The competition for Stream was around 2011 and Hikarie opened the following year. But, regardless of my own work, I remember how excited I was that it was finally about to open. Hikarie was constructed at the former site of the Tokyu Bunka Kaikan where I had gone to see my first movie, so I had very fond feelings…(laughs).

Yoshino: Everyone says that (laughs)! It seems like a lot of people have good memories of Tokyu Bunka Kaikan.

Akamatsu: When I went into Hikarie and rode up the escalator to the center of the signage ring, I felt a very uplifting feeling. I felt that a new symbol for Shibuya had been created that could promote development in the future. The building itself is also a very sharp building, and in contrast, you have the urban core that just comes out of nowhere, giving you that “aha!” moment.

Yoshino: Did you get it? (laughs) It may be that getting various pieces of information while riding the escalator--when the signage naturally catches your eye—is a new type of interactive experience with movement. Until now, people would ride on the escalators while they looked at their smartphones, but now they look around.

Shibuya Hikarie Urban Core

Shibuya Hikarie Urban Core

Okumori: Even when the master plan was created, there were discussions about one of the objectives of the urban core as a way to iron out the complexities of Shibuya and make it easier to understand. Stream Yellow is very clear in this respect.

Yoshino: I was surprised that I was able to go up the floors on one escalator in Stream’s urban core. At Hikarie, the escalator goes up from the third floor in the basement to the fourth floor above ground through commercial floors, so the escalator turns around and the lines of traffic can be messy. I thought that certainly Stream would also have a commercial area in the basement and that the escalators would go up through that area as well…

Okumori: Hikarie is connected directly to the station, so it must have been difficult to create a flow line. You must have looked at various patterns.

Yoshino: Hikarie’s urban core also connects the Fukutoshin and Ginza lines. I didn’t ask for a variety of reasons, but I would really like to see the trains running on the Ginza line from the urban core. You can hear the sounds from the Fukutoshin line and feel the breeze, but there were not many angles where I could see out directly. So, I was moved by the fact that I could see the trucks on the metropolitan expressway from Stream’s urban core and thought that the glass façade and mirrored roof were put there for that reason. It is unusual to be able to see cars driving on roads suspended in the air right from the inside of a building.

Akamatsu: That’s true. When you come up from the side of the station, you can see the yellow color of the escalator. If you follow the line of sight up, you will see the metropolitan expressway and we thought it would be great to see both activities on a mirrored monitored roof.

Okumori: Perhaps the most interesting places in Shibuya are those located next to the highway and with the Ginza line running right through it.

Yoshino: I think so. In fact, Hikarie is not completely finished yet. Going forward, we will be building a roof above the platform of the Ginza line. The sky deck above that where pedestrians can walk has finally been completed. I would like to create a flow of traffic, not only on the existing 2F deck, but also on the sky level deck to create a seamless connection between the station and the adjacent areas.

Kazuko Akamatsu

CAt Partner

Professor, Hosei University / Part-time lecturer, Kobe Design University

Shigeru Yoshino

Executive

Design Fellow