Towards a new society brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic: three challenges for medical facilities that have come to light with COVID-19

Masatoshi Oomori, Director, Project Management Dept., Client Relations Group, NIKKEN SEKKEI LTD

(The positions in this article were current at the time of publication.)

Scroll Down

Has there ever been a time where medical facilities featured so prominently in daily news? While we have all been moved by and are profoundly grateful to medical professionals in their desperate fight to save patients, these days have simultaneously been filled with a fresh sense of fear of novel infectious diseases, as the human race has had no choice but to place itself under quarantine in the face of the rampant spread of COVID-19.

In this context, it has also become evident that medical facilities, which must be able to function as the main battlegrounds in the fight against COVID-19, are in reality facing a number of problems.

Masatoshi Oomori, Director, Project Management Group, Client Relations & Solutions Department

Masatoshi Oomori, Director, Project Management Group, Client Relations & Solutions Department, NIKKEN SEKKEI LTD

Masatoshi Oomori, Director, Project Management Group, Client Relations & Solutions Department, NIKKEN SEKKEI LTD

(The positions in this article were current at the time of publication.)

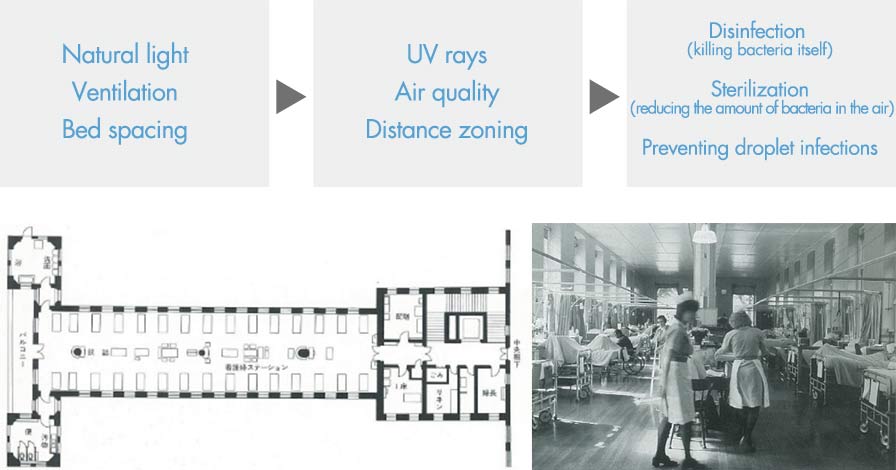

Nightingale laid the foundation for architecture to fight off infections

The founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) was the first person to introduce the idea of a sanitary environment into architecture.

Through her experience in a field hospital during the Crimean War, she became convinced that an appropriate amount of natural light, ventilation and spacing between beds were important measures against infectious diseases. Armed with this knowledge, she created the Nightingale Ward.

Figure/photo: Nightingale Ward (London, St. Thomas’ Hospital)

Figure/photo: Nightingale Ward (London, St. Thomas’ Hospital)

High-ceiling, open hospital ward with thirty beds. Windows have been set by each bed, and the topmost pane is always open for ventilation. Beds are separated at a distance of one meter or more.

Source: Hospital Architecture in Europe, Makoto Ito, Maruzen Group

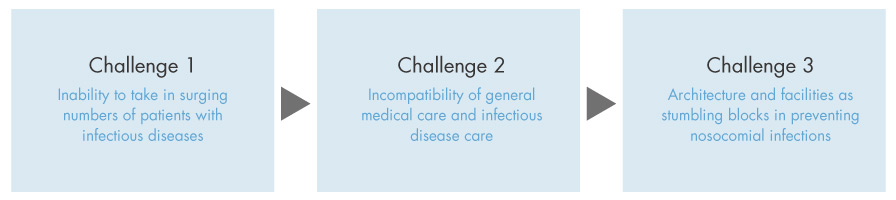

Three challenges for medical facilities revealed

As the infection spread, medical facilities that should have been equipped with the latest functions in optimal sanitary conditions were unable to take in patients in their current state, forcing hospitals to hastily throw together responses to the situation.

Amid this turmoil, there have been three major issues highlighted in the architectural design of hospitals, our first line of defense for medical care.

Relationship between Maslow’s five levels in his hierarchy of needs and the elements required for well-being and the built environment

Relationship between Maslow’s five levels in his hierarchy of needs and the elements required for well-being and the built environment

Challenge 1: Inability to take in surging numbers of patients with infectious diseases

However, there were only about 1,800 existing beds for infectious diseases at the approximately 350 hospitals around Japan designated to treat infectious diseases, indicating a severe shortage. Many of the flagship hospitals were operating at almost full capacity with a ward occupancy rate of about 95% at any given time, making it difficult to convert general wards into COVID-19 compliant wards. In addition, although there are about 7,000 beds available in Japan for critically-ill patients, there are less than 1,000 beds capable of handling ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) devices.

Modern hospitals are built with the highest priority on functionality and efficiency for medical care in normal times, meaning that, as a result, there was not enough space available in hospitals, making it difficult for them to accept patients at a moment’s notice. A major theme that needs to be addressed for the future is how spaces can be secured to smoothly admit patients when numbers spike.

Challenge 2: Incompatibility of general medical care and infectious disease care

Care for COVID-19 patients requires more manpower than regular medical care. In caring for critically-ill patients, ECMO can only be used in critical care units, such as ICUs, and the number of medical and nursing staff with specialized skills is limited, forcing general and emergency ICUs to become dedicated ICUs for COVID-19 patients and suspending general medical and emergency outpatient treatments.

Modern hospitals have been designed on the premise of not providing medical care for novel infectious diseases within general medical areas. Therefore, as the number of patients with COVID-19 rose, it became difficult for the treatment of this infectious disease to co-exist with general medical care, resulting in limitations being placed on general medical care. It will be necessary to find ways for medical facilities to be able to accept patients with infectious diseases while also avoiding suspension of general medical care services.

Challenge 3: Architecture and facilities as stumbling blocks in preventing nosocomial infections

Experts say that nosocomial infections can basically be prevented with proper hand washing and with the use of protective wear, as well as with proper zoning between infectious and non-infectious areas.

Medical facilities that received patients first zoned areas into Green, Yellow, and Red, depending on the amount of the virus present. However, since hospitals were not originally intended to be used in this way, temporary measures were taken to line the floors with tape and set up simple screens. Hospitals were forced to care for patients with an inadequate one-way flow of air from the safe and clean Green zone to the Red zone, where infected patients and suspected positive patients were located, and even in negative pressure Red zones.

Clean and dirty areas have been set up in modern hospitals and the necessary amount of ventilation in spaces is determined according to standards, but these facilities do not have adequate zoning and air flow to meet the amount of care required for novel infections. In the future, proper zoning and air conditioning systems will be required to already be in place to ensure the safe and secure care of patients with infectious diseases.

“Next Design” of medical facilities in preparation for the “next Coronavirus”

New designs will be needed for medical facilities in preparation for the next Coronavirus. To accomplish this, it is imperative that the issues for medical facilities that came to light with COVID-19 be earnestly and seriously addressed. Perhaps that design will take inspiration from Nightingale’s findings and become one that will be safe both during pandemics and comfortable in normal years, without compromising the functionality and efficiency developed by hospitals in the past.

As long as medical care continues on its journey to evolve, so too will the design of medical facilities. (September 4, 2020)

Temporary ward at Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital

Temporary ward at Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital

Concept design: Nikken Sekkei

Shielding general medical care in the main hospital ward with the construction of a COVID-19 compliant ward on an adjacent site